Monday, October 24, 2011

Wednesday, August 24, 2011

Reworking of Hansel and Gretel

http://www.chasingray.com/archives/2011/08/only_the_third_holocaust_title.html?utm_source=feedburner&utm_medium=feed&utm_campaign=Feed%3A+ChasingRay+%28Chasing+Ray%29

Because I always knew Hansel & Gretel was a Holocaust story:

I have a very high standard when it comes to reading about the Holocaust. This is not because I am personally connected to it in any way (while I had many family members fight in WWII we are not Jewish or from western Europe) (although the jury is still out on my one great grandmother's origins so this could actually change but she emigrated in the late 19th century) (more on that subject later).

Part of what bothers me about most Holocaust books (especially those written for kids and/or teens) is that they are so manipulative. The novels in some ways are the worst as they use the backdrop of a global atrocity to wring emotion out of readers that they would not receive otherwise. (Yes, I'm talking about a striped pajama boy here.) I also think we have reached a saturation point on the subject to a certain degree. I say all this just to make you understand that a Holocaust book is a very hard sell for me. The only two that have truly stayed with me over the years are Anne Frank's Diary and BRIAR ROSE by Jane Yolen. (Better than DEVIL'S ARITHMETIC in my opinion - although that is very good too, of course.) Then over the weekend I finally read KINDERGARTEN by Peter Rushforth and it was simply one of the most impressive books I have ever read. Period.

Rushforth approaches his subject from the side - there's almost a WG Sebald type feel to how he tells this story. The protagonist, "Corrie" (for Cornelius) is a 16 year old British boy in 1978. He and his two younger brothers live in the countryside with their father, headmaster of a nearby boarding school, in a house next door to their grandmother. The book is set over the Christmas holidays the same year that the boys lost their mother in an airline hijacking in Rome. Their father has gone to the US for a fund raising drive to help terror victims organized by other families of those on the plane and thus the boys are with their grandmother, who was originally born in Germany but lived in England since just prior to WWII. When she was younger, Lilli was a renowned artist of fairy tale paintings. She stopped painting after moving to England but lately her work is receiving some new appreciation. Over the years she has given the family some of her old work and Corrie has a picture she did for Hansel and Gretel on his bedroom wall. The painting and the German poem "Kinderstimmen" by Joseph von Eichendorff have inspired Corrie, a talented musician, to compose a song. His ongoing work on the piece is what prompts much of the book's ruminations on "Hansel and Gretel" and other fairy tales of lost children.

At the family settles in for Lilli's traditional German Christmas celebration, they are also riveted by another terrorist nightmare going on in West Berlin. A group has taken over a school and promised to start killing children if some of their comrades are not released from prison. The authorities, of course, are refusing to do so. The standoff is being covered on the television and has caused the boys, already missing their mother so much, to mourn her anew.

For Corrie, all of this, his own now motherless siblings, the lost children in the fairy tale, the children in the school, is powerful stuff. He and his brother Jo have fallen into a habit of comedy to cope with their sorrow but both are aware of how deep their feelings go. Jo in particular is struggling mightily and Corrie wants to help him but is not sure how. To keep himself distracted he has become obsessed with a cache of old files he has found in the school's music room where he goes each day to work on his composition. (The school is empty for the holidays but he has his father's keys and permission.) The letters are from German Jewish families who desperately tried to send their children to the school in the mid to late 1930s. At first they went simply to continue the education that was then denied them in Germany but increasingly the letters became more and more emotional as the parents lose access to the money they need to pay tuition and fees but their need to keep their children out of Germany only intensifies. At one point Corrie reads a letter from a little girl who was homesick and after the holidays has decided not to return to school. It is 1938 and her family decides to seek shelter in another country. Rushforth writes:

In October a postcard had come from the Goetzels saying that they are safe in Amsterdam, and that was the last communication the family made with the school.

Anne Frank and her family had been German refugees in Amsterdam.

All of this, Corrie's music, Lilli's mysterious past, little brother Jo devastated by his mother's death, the hostages in West Berlin, the letters, spread across the floor in the music room charting the lives and potential deaths of the Jewish children decades before, all of this comes together in a whirl and a swirl that includes excerpts from "Hansel and Gretel" and Lill's final, unsurprising but utterly heartbreaking, revelation about what she left behind in Germany so many years before. Corrie learns just how close his own life is to those he found in the letters and to the children in the fairy tale. And even though you suspected this was coming, on some level, still all of it together is so beautifully written, so wonderfully wrought, that it reaches you in a far deeper way than you expected.

It's like that passage in the Holocaust Museum in DC. It is all very obvious there (of course) with the train car and the compressed passageways to give you the feeling of being forced into a tight space, and the recorded oral histories and the many displays of propaganda and artifacts. But then there is this light filled passage, a bridge actually, you walk across and the walls are lined with black and white photos of all sizes and they stretch up for several stories and they are all of different people in different settings. Happy, sad, group shots, class pics, just standard photos that any album from the 1930s or 40 would have. And then you read at the end that all of these people lived in the same village and all of them - all of them - were killed by the Nazis. The village is gone. And so you look back now, you study them more carefully, you consider them for all their sameness to you and yours and in that moment, for me anyway, the reality of the Holocaust hits home. The big number is almost too big to wrap your head around but this much smaller number, this tiny village with all those faces, is one you can see and feel. It is one that makes sense of the entire six million.

In KINDERGARTEN Corrie knows about the Holocaust just as he knows about the Magna Carta and the Battle of Hastings. These are things, he thinks, that every school child knows so they can be ready for test - the dates, the locations, the figures. But reading the letters in the school, getting to know the families through the children who made it out and those who kept trying and then vanished, is what makes the history real to him. Just like the sight of the small girl in the window of the West Berlin school is what terrorism is really all about, just like their mother, just like Hansel and Gretel.

Just like, of course, the story Lilli tells her grandsons in the book's final pages.

Peter Rushforth was a master storyteller, a truly amazing writer. KINDERGARTEN appeared on my radar years ago after a most favorable mention by Terri Windling. I'm so glad I finally read it. As a reader it is amazing but as a writer it is by far one of the best examples of our craft that I have ever come across. Life changing.

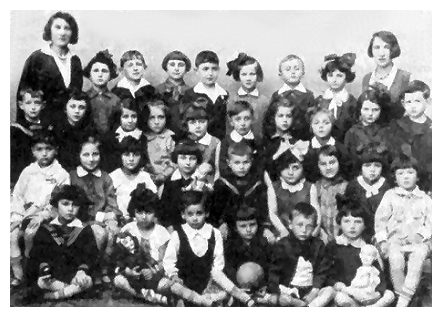

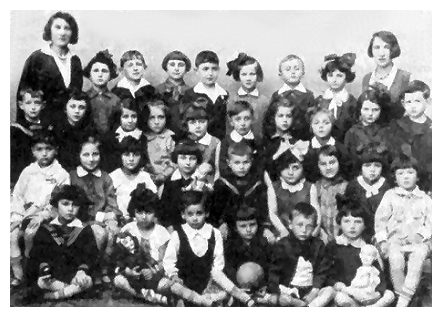

[Post pic: The kindergarten of Maria and Roman Ginzberg, class of 1930, Piorkow Trybunalski, Poland and photo entitled "Urban Hansel & Gretel" - the person who took it is now lost due to a dead link, sadly.]

Because I always knew Hansel & Gretel was a Holocaust story:

I have a very high standard when it comes to reading about the Holocaust. This is not because I am personally connected to it in any way (while I had many family members fight in WWII we are not Jewish or from western Europe) (although the jury is still out on my one great grandmother's origins so this could actually change but she emigrated in the late 19th century) (more on that subject later).

Part of what bothers me about most Holocaust books (especially those written for kids and/or teens) is that they are so manipulative. The novels in some ways are the worst as they use the backdrop of a global atrocity to wring emotion out of readers that they would not receive otherwise. (Yes, I'm talking about a striped pajama boy here.) I also think we have reached a saturation point on the subject to a certain degree. I say all this just to make you understand that a Holocaust book is a very hard sell for me. The only two that have truly stayed with me over the years are Anne Frank's Diary and BRIAR ROSE by Jane Yolen. (Better than DEVIL'S ARITHMETIC in my opinion - although that is very good too, of course.) Then over the weekend I finally read KINDERGARTEN by Peter Rushforth and it was simply one of the most impressive books I have ever read. Period.

Rushforth approaches his subject from the side - there's almost a WG Sebald type feel to how he tells this story. The protagonist, "Corrie" (for Cornelius) is a 16 year old British boy in 1978. He and his two younger brothers live in the countryside with their father, headmaster of a nearby boarding school, in a house next door to their grandmother. The book is set over the Christmas holidays the same year that the boys lost their mother in an airline hijacking in Rome. Their father has gone to the US for a fund raising drive to help terror victims organized by other families of those on the plane and thus the boys are with their grandmother, who was originally born in Germany but lived in England since just prior to WWII. When she was younger, Lilli was a renowned artist of fairy tale paintings. She stopped painting after moving to England but lately her work is receiving some new appreciation. Over the years she has given the family some of her old work and Corrie has a picture she did for Hansel and Gretel on his bedroom wall. The painting and the German poem "Kinderstimmen" by Joseph von Eichendorff have inspired Corrie, a talented musician, to compose a song. His ongoing work on the piece is what prompts much of the book's ruminations on "Hansel and Gretel" and other fairy tales of lost children.

At the family settles in for Lilli's traditional German Christmas celebration, they are also riveted by another terrorist nightmare going on in West Berlin. A group has taken over a school and promised to start killing children if some of their comrades are not released from prison. The authorities, of course, are refusing to do so. The standoff is being covered on the television and has caused the boys, already missing their mother so much, to mourn her anew.

For Corrie, all of this, his own now motherless siblings, the lost children in the fairy tale, the children in the school, is powerful stuff. He and his brother Jo have fallen into a habit of comedy to cope with their sorrow but both are aware of how deep their feelings go. Jo in particular is struggling mightily and Corrie wants to help him but is not sure how. To keep himself distracted he has become obsessed with a cache of old files he has found in the school's music room where he goes each day to work on his composition. (The school is empty for the holidays but he has his father's keys and permission.) The letters are from German Jewish families who desperately tried to send their children to the school in the mid to late 1930s. At first they went simply to continue the education that was then denied them in Germany but increasingly the letters became more and more emotional as the parents lose access to the money they need to pay tuition and fees but their need to keep their children out of Germany only intensifies. At one point Corrie reads a letter from a little girl who was homesick and after the holidays has decided not to return to school. It is 1938 and her family decides to seek shelter in another country. Rushforth writes:

In October a postcard had come from the Goetzels saying that they are safe in Amsterdam, and that was the last communication the family made with the school.

Anne Frank and her family had been German refugees in Amsterdam.

All of this, Corrie's music, Lilli's mysterious past, little brother Jo devastated by his mother's death, the hostages in West Berlin, the letters, spread across the floor in the music room charting the lives and potential deaths of the Jewish children decades before, all of this comes together in a whirl and a swirl that includes excerpts from "Hansel and Gretel" and Lill's final, unsurprising but utterly heartbreaking, revelation about what she left behind in Germany so many years before. Corrie learns just how close his own life is to those he found in the letters and to the children in the fairy tale. And even though you suspected this was coming, on some level, still all of it together is so beautifully written, so wonderfully wrought, that it reaches you in a far deeper way than you expected.

It's like that passage in the Holocaust Museum in DC. It is all very obvious there (of course) with the train car and the compressed passageways to give you the feeling of being forced into a tight space, and the recorded oral histories and the many displays of propaganda and artifacts. But then there is this light filled passage, a bridge actually, you walk across and the walls are lined with black and white photos of all sizes and they stretch up for several stories and they are all of different people in different settings. Happy, sad, group shots, class pics, just standard photos that any album from the 1930s or 40 would have. And then you read at the end that all of these people lived in the same village and all of them - all of them - were killed by the Nazis. The village is gone. And so you look back now, you study them more carefully, you consider them for all their sameness to you and yours and in that moment, for me anyway, the reality of the Holocaust hits home. The big number is almost too big to wrap your head around but this much smaller number, this tiny village with all those faces, is one you can see and feel. It is one that makes sense of the entire six million.

In KINDERGARTEN Corrie knows about the Holocaust just as he knows about the Magna Carta and the Battle of Hastings. These are things, he thinks, that every school child knows so they can be ready for test - the dates, the locations, the figures. But reading the letters in the school, getting to know the families through the children who made it out and those who kept trying and then vanished, is what makes the history real to him. Just like the sight of the small girl in the window of the West Berlin school is what terrorism is really all about, just like their mother, just like Hansel and Gretel.

Just like, of course, the story Lilli tells her grandsons in the book's final pages.

Peter Rushforth was a master storyteller, a truly amazing writer. KINDERGARTEN appeared on my radar years ago after a most favorable mention by Terri Windling. I'm so glad I finally read it. As a reader it is amazing but as a writer it is by far one of the best examples of our craft that I have ever come across. Life changing.

[Post pic: The kindergarten of Maria and Roman Ginzberg, class of 1930, Piorkow Trybunalski, Poland and photo entitled "Urban Hansel & Gretel" - the person who took it is now lost due to a dead link, sadly.]

Wednesday, August 3, 2011

Ballad Spotting: Thomas the Rhymer

From: Feature Interview: Seanan McGuire

http://www.fantasy-magazine.com/new/new-nonfiction/feature-interview-seanan-mcguire/

I studied folklore in college, and I’m still studying it now, as an adult. I expect to be studying folklore for the rest of my life. With that in mind, I truly believe that the current blurring of the borders between fantasy, horror, and romance are not representative of a mutation; they’re representative of a bunch of walls we didn’t really need finally coming down. The oldest stories we have were, at the time, what we would classify as “urban fantasy” today. Thomas the Rhymer? His mother was dead when he was conceived, and he was carried to term in her coffin (horror). He fell in love with the Queen of Faerie, calling her “Queen of Heaven” and charming her heart (romance). So she took him to the fairy lands to dwell by her side (fantasy), even though they had to wade through red blood to the knee to get there (horror). Eventually, he chose to leave her to return to his own kind, and she cursed him with honesty (fantasy). In the end, he returned to her, and to Faerie, forevermore (romance). When this story was new, the settings it used were as familiar to the people who heard it as Chicago or Melbourne or San Francisco will be to modern readers of urban fantasy.

In some of the oldest forms of the Snow White/Rose Red story, there’s a third sister, Lily Fair. I like to say that urban fantasy writers are the Children of Lily Fair, the ones seeking the balance between Snow White’s fantasy and Rose Red’s horror. We’re the place where the lines drop away, and that’s a beautiful place to be.

Tuesday, August 2, 2011

Ballad spotting: The Mermaid: Child Ballad 289

http://surlalunefairytales.blogspot.com/

The Mermaid: Child Ballad 289: "

One of the side benefits of working on the SurLaLune fairy tale anthologies is that I am becoming more familiar with various Child Ballads. While I enjoy ballads, they hadn't inspired much research on my part until the last few years. (There just isn't the time to do everything that interests me!)

I previously posted about Clerk Colvill, Child Ballad 42, which I enjoyed as I edited Mermaid and Other Water Spirit Tales From Around the World . The other ballad I included in the collected is Child 289 and I personally prefer it over Clerk Colvill. Most commonly known as The Mermaid, seven versions from Child appear in my book under various titles, including Greenland, The Seaman's Distress, and The Stormy Winds Did Blow. As I read it, Iwanted to listen to it, so I hunted some versions down on the internet.

. The other ballad I included in the collected is Child 289 and I personally prefer it over Clerk Colvill. Most commonly known as The Mermaid, seven versions from Child appear in my book under various titles, including Greenland, The Seaman's Distress, and The Stormy Winds Did Blow. As I read it, Iwanted to listen to it, so I hunted some versions down on the internet.

Here's the text to Child 289B, which more closely resembles many of the modern recorded versions. Actually, most of them tend to be a hybrid of 289A, 289B and 289C. The ballad draws from the superstition that when sailors spy a mermaid, a shipwreck is imminent.

One of my favorite versions isn't a recording for purchase, but a homemade video on YouTube which I am embedding below. I enjoyed the simplicity of the tune and the variations it offered on the ballad itself. Here it is:

As for recorded versions available for download, I preferred The Mermaid Song by the Floorbirds.

by the Floorbirds.

Other versions you might prefer include The Mermaid by The Pirates of St. Piran and The Mermaid

by The Pirates of St. Piran and The Mermaid by Celtic Stew.

by Celtic Stew.

"

"

The Mermaid: Child Ballad 289: "

One of the side benefits of working on the SurLaLune fairy tale anthologies is that I am becoming more familiar with various Child Ballads. While I enjoy ballads, they hadn't inspired much research on my part until the last few years. (There just isn't the time to do everything that interests me!)

I previously posted about Clerk Colvill, Child Ballad 42, which I enjoyed as I edited Mermaid and Other Water Spirit Tales From Around the World

. The other ballad I included in the collected is Child 289 and I personally prefer it over Clerk Colvill. Most commonly known as The Mermaid, seven versions from Child appear in my book under various titles, including Greenland, The Seaman's Distress, and The Stormy Winds Did Blow. As I read it, Iwanted to listen to it, so I hunted some versions down on the internet.

. The other ballad I included in the collected is Child 289 and I personally prefer it over Clerk Colvill. Most commonly known as The Mermaid, seven versions from Child appear in my book under various titles, including Greenland, The Seaman's Distress, and The Stormy Winds Did Blow. As I read it, Iwanted to listen to it, so I hunted some versions down on the internet.Here's the text to Child 289B, which more closely resembles many of the modern recorded versions. Actually, most of them tend to be a hybrid of 289A, 289B and 289C. The ballad draws from the superstition that when sailors spy a mermaid, a shipwreck is imminent.

ONE Friday morn when we set sail,

Not very far from land,

We there did espy a fair pretty maid

With a comb and a glass in her hand, her hand, her hand,

With a comb and a glass in her hand.

While the raging seas did roar,

And the stormy winds did blow,

While we jolly sailor-boys were up into the top,

And the land-lubbers lying down below, below, below,

And the land-lubbers lying down below.

Then up starts the captain of our gallant ship,

And a brave young man was he:

“I’ve a wife and a child in fair Bristol town,

But a widow I fear she will be.”

For the raging seas, etc.

Then up starts the mate of our gallant ship,

And a bold young man was he:

“Oh! I have a wife in fair Portsmouth town,

But a widow I fear she will be.”

For the raging seas, etc.

Then up starts the cook of our gallant ship,

And a gruff old soul was he:

“Oh! I have a wife in fair Plymouth town,

But a widow I fear she will be.”

And then up spoke the little cabin-boy,

And a pretty little boy was he;

“Oh! I am more grievd for my daddy and my mammy

Than you for your wives all three.”

Then three times round went our gallant ship,

And three times round went she;

For the want of a life-boat they all went down,

And she sank to the bottom of the sea.

One of my favorite versions isn't a recording for purchase, but a homemade video on YouTube which I am embedding below. I enjoyed the simplicity of the tune and the variations it offered on the ballad itself. Here it is:

As for recorded versions available for download, I preferred The Mermaid Song

by the Floorbirds.

by the Floorbirds.Other versions you might prefer include The Mermaid

by The Pirates of St. Piran and The Mermaid

by The Pirates of St. Piran and The Mermaid by Celtic Stew.

by Celtic Stew.Friday, July 29, 2011

Fairytale Reflections (29) Sally Prue

Fairytale Reflections (29) Sally Prue: "

"

"

When Sally Prue’s first novel, ‘Cold Tom’ won the Branford Boase Award and the Smarties Prize Silver Award in 2002, it was clear that a wonderful new writer of folklore-based fantasy had arrived. ‘Cold Tom’ taps into many legends and ballads about the fairies - the Tribe, which lives on the common. They are cold-hearted, dangerous, feral hunters, pitiless to those who, like Cold Tom himself, are different. And they see humans as demons: ugly lumpen beings, hopelessly tied and enslaved to one another by a tangle of emotional bonds like vines.

It’s a powerful and startling image, and one of those moments only fantasy provides: when we step right out of the human world and see it from outside, like seeing the Earth from space. Cold Tom is only half elfin. His fangs aren’t growing, the Tribe rejects him, and the only place to run is the city of the demons. How on earth can he adjust to humanity and the ties that bind us?

Sally’s writing reminds me of Diana Wynne Jones who wrote books of otherworldly beauty – I’m thinking of ‘Power of Three’ and ‘The Spellcoats’ – as well as more homely and amusing stories for younger readers, such as the Chrestomanci books. ‘Cold Tom’ and its recent sequel (or more accurately prequel) ‘Ice Maiden’ are YA reads: chilling, haunting, sharp-edged. Here young half-German Franz, who has fallen into a pit on the common while chasing the elfin Edrin, finds a heap of elfin bones, and prods the skull:

This time there was no doubt: the white bone moved. More than that, it gave way, swiftly, bewilderingly, and before he could stop it his finger had gone right through the bone into the brain cavity.

He snatched his hand back in horror, but somehow, horribly, the whole skull came with it. Panicking, he tried to bat the thing off with his other hand, but those fingers sank into the stickily melting bone of the skull, too.

And suddenly Franz’s head was full of savage laughter, and glowing eyes, and dangerous darkness.

And singing.

Sally is also the author of a trilogy of books for younger, ‘middle grade’ readers: the Truth Sayer Trilogy. As Sally comments on her website: “You know how people are always going into a different world and then discovering that everyone speaks English? Well, what if they don’t?”

I love this. Young Nian is taken away from his family by the Tarhun, warrior priests, to be trained as a seer and Truth Speaker at the House of Truth on the Holy Mountain. Nian may have great powers, but he misses his family and finds the stern House little better than a prison. So he tries to escape. This sounds like the stuff of many other fantasy novels, but Sally’s sense of humour and strong characterisation distinguish Nian’s erratic career across the universes, landing in our own world – Earth – in the bedroom of a very ordinary boy called Jacob. Neither can understand a word the other says, and comic mayhem follows. In a way, it’s the same theme as the Cold Tom books: looking at our world from outside, seeing ourselves as others see us. The trilogy also encompasses a variety of thought-provoking ideas about the nature of time and space, and besides the comedy, there are some tremendous moments of imagination and terror: as in the second book of the trilogy, the March of the Owlmen, when the knife-sharp, two-dimensional Owlmen come slicing into the world.

So welcome to Sally Prue, who is going to talk about searching for fairyland and finding it (maybe) closer than you expected: in the mirror, out in the yard, around the back of the supermarket carpark. For as Franz thinks to himself at the beginning of ‘Ice Maiden’ – ‘This wasn’t a folk tale, this was 1939. There were no elves or fairies here, any more than there were wolves. It was impossible, completely impossible, there could be any kind of creature anywhere near him… And at this same moment something hit him violently in the back.’

THE ENCHANTED MIRROR

We didn’t lack books in my childhood home. I mean, we had a Bible, a Be-Ro cookery book, David Copperfield, Shakespeare, and, oddly, the collected poems of Walter de la Mare.

Mind you, of these only the cookery book was ever actually opened.

But we had a large blue set of Arthur Mee’s Children’s Encyclopaedias, too. I think they must have been my father’s. They were from the 1930s and extremely dull. Occasionally, though, the pages of dense text and murky photographs of the Queen Mary’s turbines were enlivened by brief re-tellings of classic tales.

Now, I must be honest here. As a child I had no taste. What I wanted from a story was, first of all a HAPPY ENDING, and secondly REALLY NICE CLOTHES. Ideally that meant princesses, but even a goose girl would do as long as her rags were elegantly tattered and her apron strings were blown into delectable volutes.

I very happily read all Arthur Mee had to say about Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty and The Ugly Duckling (a great favourite: I was the only girl in my class without fair hair and so I was constantly cast as the witch in our singing games. But oh, I thought, perhaps one day...).

Those were important stories. They introduced me to beauty in art. They taught me that the values of my family were not the values of the whole world. They taught me to hope.

For the time being, though, I was young, and therefore enslaved and helpless. To make matters worse the land of the princesses was plainly very far away. I knew of no real-life princesses except Princess Anne, and she seldom appeared swathed in acres of bouncing chiffon, which was surely the entire point of being a princess.

(Actually, Princess Anne never appeared in acres of bouncing chiffon. I just couldn’t begin to understand it. Reefer jackets?)

Now, unfortunately, Arthur Mee’s stories were not very many, and not very long, and I soon began to suffer from serious princess-starvation. Looking back, I can see that in the man’s world of the 1930s Arthur Mee had been generous to include any princesses at all. They were probably as unappealing to him as the Queen Mary’s innards were to me. But there it was: all too soon a thoroughly satisfactory story like Snow White would be followed by something about Camelot or Olympus which were dull dull dull, with few happy endings and fewer princesses, and those there were dressed in either their nighties (Olympus) or their dressing gowns (Camelot).

I realise that so far I have proved myself to have been the dullest, least numinous sort of child (so lacking in genius that I was quite unable to make anything at all of David Copperfield, Shakespeare, or Walter de la Mare) but I’m sorry to say that things are about to get even worse, because for my seventh Christmas my Cousin Ann bought me a copy of Chimney Corner Stories by Enid Blyton.

Now, I don’t think there are any princesses at all in Chimney Corner Stories, and Enid Blyton isn’t really interested in clothes, either: there’s one really shocking tale about a doll who cuts up her lace coat to make some curtains for a dolls house, an act of madness of which the author seems, astonishingly, to approve.

Still, Enid Blyton’s stories are solidly constructed and I found them extremely satisfying. By far the most marvellous thing of all, though, was that in several of the stories the elves come out of fairyland into our own world. One elf gives wishes to ordinary children (and I was, as we have seen, a very ordinary child) and another (actually I think it might have been a goblin) is banished from fairyland for wickedly stealing hairs from caterpillars to make paint brushes.

Now that was truly astonishing, because it meant that fairyland couldn’t far away at all. Those elves and gnomes were coming and going from fairyland to my world just as easily as I left home to go to school.

Think of that! Snow White’s country was clearly a long way away (and once upon a time, as well) but these gnomes were emerging from their fairyland straight into contemporary England – a rather smug version of contemporary England which included servants and ponies, true, but recognisable for all that.

Not only that, but when I looked at the fairies’ clothes (always the clothes!) I saw that some of them were wearing bellbine hats. Now, bellbine grows along municipal chain-link fencing everywhere in England. Why, bellbine even grew through the hedge between my house and the plastic bag factory!

And if there were bellbine flowers, then perhaps...well, even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (as I learned from the children’s TV programme Blue Peter) had believed there might be fairies at the bottom of the garden.

I searched and searched among the bellbine, and occasionally I saw something, or just missed seeing something, or heard a mysterious rustling, which might have been a fairy. It was enough to keep my new hopes alive.

When I got to the junior school I had access to more books, and my horizons widened accordingly. I learned about the wardrobe, of course (my parents’ wardrobe contained not one single fur coat and perhaps that was why it proved a continuing disappointment) and later, I suppose by this time at secondary school, I learned about Herne the Hunter in Windsor Great Park, and the god (or goddess) Sul who lives in the hot spring at Bath.

I learned about a very local haunting, Harcourt’s Chariot, which rattles precipitously down the Back Hollow from Ashridge to Aldbury.

I learned about the Romans’ lares and penates which guard boundaries and households. I found out about the green men who have been hiding in the foliage around us for so long that no-one knows any longer where they came from or why they are watching us.

This intrusion of otherworldly beings into my own England was startlingly different from the stories of Camelot and Olympus, and different from the stories of the princesses, too. Herne and Harcourt and the green men were here, now, close as breathing, casting shadows on my back. Mount Olympus might be a real place, but it was far beyond my reach (I’m sorry to say that the furthest we’d ever gone on a family holiday was Lyme Regis).

In any case, to visit the Olympians you needed Hermes’ wings, or Iris’s rainbow: there was no way, even in my wildest fantasies, I was going to find Apollo mooching about round the back of a plastic bag factory. (I admit that nymphs seemed to get about a bit, but nymphs were like Star Trek security men: shallow in character and soon dead.)

I was realistic enough to know, anyway, that even if I could get to Olympus or glum Camelot then none of those grand people – Lancelot or Zeus or Morgan Le Fay or Hera – was going to be the slightest bit interested in me. (If Adele Geras’s marvellous stories of the Greek gods had been available I might have felt differently about this, but, alas, they were yet to be written.)

So that left me with Herne the Hunter and various ghosts, pixies and green men – none of them, frankly, either snoggable or the sort of people you could take home to meet your parents. My interest in fairyland wobbled.

But then one day a boyfriend said do you like folk music? and put on a record. It was a song about a real place, Carterhaugh, where it is so easy to pass from England to fairyland that the tale begins with a warning:

Oh I forbid you, maidens a’

That wear gowd in your hair,

To come or gae by Carterhaugh

For young Tam-lin is there.

Tam-lin. And suddenly there it was, opening before me: a handsome prince grown close and dangerous, stepping out of the pages of a book and onto the real earth of my own country.

Janet has kilted her green kirtle

A little aboon her knee...

And she’s awa to Carterhaugh

As fast as she can hie.

And who, frankly, can blame her?

Oh yes, and suddenly the roots of fairyland were growing out and penetrating into real life again, into my life, for Janet is no beflounced princess, but a woman of warm blood and hot desire who knows what she wants and is prepared to fight to get it.

Yes. I discovered I was now old enough to journey far – and fight for what I wanted, too.

Fairyland had grown, just as I had, and yet again, like an enchanted mirror, it was showing me not my own reflection but my heart’s desire. Over the years it had presented to me visions of beauty, hope, escape, romance, and in the end courage.

And I’ll tell you something. That boyfriend never got away.

Picture credits:

Sally Prue

Tam Lin copyright Dan Dutton

Princess Anne in The Courier

The Convulvulous Fairy by Cicely Mary Barker

Picture credits:

Sally Prue

Tam Lin copyright Dan Dutton

Princess Anne in The Courier

The Convulvulous Fairy by Cicely Mary Barker

Friday, July 1, 2011

Ballad Sptting: Tam Lin

The ballad of Tam Lin is played out, with role reversals, as part of the subplot of Seanan McGuire's An Artificial Night: An October Daye Novel (Daw, 2010).

Everyone in the Bay Area knows about Blind Michael, the unseen, dangerous figure whose Hunt sweeps the Berkeley hills on full moon nights. He's a familiar hazard of life in the Kingdom of the Mists, and most people don't waste time worrying about him. October "Toby" Daye certainly doesn't. She has better things to worry about, like paying the electrical bill on time. So it's understandable that she'd be upset when Blind Michael suddenly starts taking an interest in people that matter to her, like the youngest children of Mitch and Stacy Brown.

Tasked to find the missing children, and with the stakes growing higher by the minute, Toby has few choices and fewer allies to help her through the dangers yet to come. With the Luidaeg's help and a candle to light her way home, there's a chance that she'll come through this latest danger...but the sudden appearance of her Fetch doesn't give Toby all that much in the way of hope...

An Artificial Night is the third book in the October Daye series, a modern urban fantasy set in both the San Francisco Bay Area and the Faerie Kingdom of the Mists which overlays Northern California.

[http://www.seananmcguire.com/aan.php]

Everyone in the Bay Area knows about Blind Michael, the unseen, dangerous figure whose Hunt sweeps the Berkeley hills on full moon nights. He's a familiar hazard of life in the Kingdom of the Mists, and most people don't waste time worrying about him. October "Toby" Daye certainly doesn't. She has better things to worry about, like paying the electrical bill on time. So it's understandable that she'd be upset when Blind Michael suddenly starts taking an interest in people that matter to her, like the youngest children of Mitch and Stacy Brown.

Tasked to find the missing children, and with the stakes growing higher by the minute, Toby has few choices and fewer allies to help her through the dangers yet to come. With the Luidaeg's help and a candle to light her way home, there's a chance that she'll come through this latest danger...but the sudden appearance of her Fetch doesn't give Toby all that much in the way of hope...

An Artificial Night is the third book in the October Daye series, a modern urban fantasy set in both the San Francisco Bay Area and the Faerie Kingdom of the Mists which overlays Northern California.

[http://www.seananmcguire.com/aan.php]

Labels:

Ballads,

folklore in popular culture,

reworkings,

Tam Lin

Monday, May 30, 2011

Sunday, May 1, 2011

Folklore in Popular Culture

For the last umpteen years I have had my storytelling students do an assignment on finding and discussing folklore in popular culture. Due to budget cuts, I will not be teaching the storytelling course at the university this year so decided to share some of the findings on this blog. In the comics this morning, I found three examples: one from the world of folktale, the second a proverb, and the third from mythology.

1] I don't think I need to explain this one...http://comics.com/the_other_coast/ (May 1, 2011)

http://www.theargylesweater.com/ (May 1, 2011)

http://comics.com/reality_check/ (May 1, 2011)

1] I don't think I need to explain this one...http://comics.com/the_other_coast/ (May 1, 2011)

http://www.theargylesweater.com/ (May 1, 2011)

http://comics.com/reality_check/ (May 1, 2011)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)